ARAS Connections: Image and Archetype - 2019 Issue 1

I first came across Caterina Vezzoli’s exceptional work in her chapter, "Queens, Saints, Heretics, Prostitutes: Women in Italy" that she wrote for Europe’s Many Souls which I co-edited with Joerg Rasche. I found that traveling along with her imaginative exploration of Italian women through history was thrilling and compelling. In the final sentence of “Le Genre à l’Oeuvre” which appears in this edition of ARAS Connections, I found myself nodding in agreement that what she writes is not only true for her, but through her, for every reader who joins in her journey: "To combine analytical psychology, history and art is a way to rejuvenate my psyche and my understanding of the world of women.”

The "understanding of the world of women" that Vezzoli communicates in writing makes clearer to both men and women the price women have paid over the millennia at the hands of the patriarchy and simultaneously the enormously glorious contribution women have made to the expression of eros in art and in the spiritual life. I have often recoiled at how the use of the word “patriarchy” has become something of a politically correct cliche that obscures rather than fosters understanding. With Vezzoli’s writing, I find myself easily embracing her condemnation of "the patriarchy" and the price both women and men have paid under its oppressive reign.

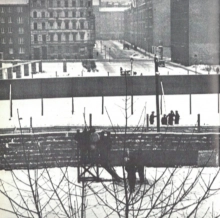

A different type of wall from that which has divided men and women through the ages is that which Jung noted in Man and His Symbols when he wrote about the Berlin Wall: “Our world is dissociated like a neurotic."

It has been reported that Man and His Symbols was conceived by Jung in response to a dream he had in which his work was understood by a wider public. Although it remains mostly an unrealized dream, many of us believe that Jung’s approach to symbols should be of the greatest interest to a broad audience because symbols in public life move us so powerfully.

Because symbols are polyvalent, it is important to try not to be one-sided or partisan in our approach to them. That is very hard in a highly partisan time and perhaps no contemporary evocation of a symbol has been more divisive than “the Wall.” In the article that I have contributed to this edition of ARAS Connections I did my best to take a non partisan approach to the powerful symbol of the wall, while simultaneously making clear my own political stance. We walk a tightrope when we both acknowledge our own political point of view while also trying to understand in good faith what motivates our political opponents. But, we must acknowledge that symbols move us deeply in the public sphere and we should not shy away from trying to understand the depth of their meaning that speaks to many people, no matter which side of the wall as symbol they stand on.

Le Genre à l’Oeuvre

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to combine modern women’s art with feminine mysticism of the Middle Ages and “minor” artistic artefacts done by nuns living in convents during the first three centuries of the first millennium.

Reflection on women’s artistic expression is a long-time interest of mine that found its moment of grace at “Les Papesses” exhibition in the Avignon Palace of the Popes in 2013. The real blossoming of this interest was expressed at the Art and Psyche conference in Sicily where I presented some of the material in this paper.

Avignon

In 2013 an exhibition in Avignon at the Palace of the Popes, “Les Papesses”, put forth the question of discrimination in the art world towards women artists. The newspaper Le Monde, where I first read about the exhibition, titled the article “L’art est un bastion sexiste” – Art is a sexist stronghold. The title of the exhibition, compared with the historical meaning of the Avignon palace, seemed to me a declaration of war against the power exerted on women for many centuries by the dominant patriarchal culture.

Women’s art had always been considered inferior. Since the Middle Ages the artistic production of women, mainly nuns and upper-class women, was overlooked. Women’s artistic works couldn’t be exhibited in general and the works produced by nuns--tapestries, paintings or other works--had to be kept in an enclosure where only the nuns could see them. However, the best poetry of the period was composed by women. Moreover, in recent years the richness of nuns’ medieval artistic production has been recognized by scholars studying medieval art.

The location of the exhibition, the palace of Avignon, is in itself a demonstration of masculine power with no concession to roundness or greenery (Fig. 1). Built in stone, with tiny dark corridors, narrow and steep staircases, hidden passages that even today are difficult to detect, hint at treacherous conspiracies, cold spaces, indescribable tortures and the ostentatious show of power. The struggle for domination is written on every stone.

The exhibition of the women artists and their visions there suggested that the palace had been conquered by the suffering bodies of the “inferior beings”. One of the places where the patriarchal dominant power had projected on women all the wrongs and all the infamies that could be imagined, was now conquered.

The other hint to a change in perspective from patriarchal power to the recognition of the diversity of the feminine power is in the title “Les Papesses”, the women Popes; the reference is from the legend of Pope Joan who was very popular at the end of first millennium. One of the early chronicles of this legend tells that Pope Joan disguised her feminine identity and reigned for a few years between 850 and 900. The years of her reign were peaceful and just.

At the 2013 exhibition, Maman, Louise Bourgeois’ spider and Jana Sterbak’s spheres (Fig. 2) were awaiting the visitors.

Bourgeois’ spider is the archetypal summa of all the prejudice against women. At the same time, Maman powerfully reminds us of the unconscious fear of feminine power as well as the capacity to repair the broken threads of relationships by the patient weaving of the canvas. The roundness of Sterbak’s spheres is perfection that asks to be explored. The five contemporary artists, Louise Bourgeois, Berlinde De Bruyckere, Camille Claudel, Kiki Smith and Jana Sterbak, developed their artistic visions around archetypal themes coming from fairy tales, from the juxtaposition of religious art work of the past, from descriptions of the distress, fear and suffering that have accompanied and are always present in the lives of women.

What walls symbolize: We must understand their meaning to appreciate the power of what's at the center of the shutdown

This article first appeared as an op-ed piece in the New York Daily News.

After President Trump’s recently departed chief of staff, John Kelly, suggested that the border wall his former boss demands wasn’t actually a wall, Sen. Lindsay Graham added that the wall is merely “a metaphor for border security.” All the President’s men tried to "walk back” the wall, but Trump would have none of it. Perhaps that’s because he knows the difference between a symbol and a metaphor, and he wanted to reaffirm the symbolic weight of the word “wall” that he has been erecting in the American psyche since 2016.

More than a metaphor, the wall is a symbol. And, when a symbol becomes potent enough to shut down the government, we should pause to review what a symbol is, and how Trump’s wall operates as such. In so doing, we may better understand the furor and monumental impasse it has created.

A symbol’s power lies in its polyvalency: it can evoke many simultaneous emotions and meanings, even contradictory ones. And a symbol can accrue meaning over time, such as the American flag, the Christian cross or the Nazi swastika, so that history adds to its gravitas. A symbol’s power to move people comes from its ability to tap the depths of the human psyche, where primitive, non-rational emotions lie dormant, waiting to be roused.

Trump’s wall draws part of its symbolic power from the long human history with walls. The Soviets built the Berlin Wall to keep citizens in, while the Chinese used the Great Wall to keep the Mongols out. Trump’s proposed wall is intended to keep dangerous people, such as terrorists and criminals, at bay. There are also racist and ethnic currents in the motivation to build Trump’s wall, as it would fulfill his campaign promise to keep “bad hombres” out of the country.

Thus Trump’s wall arouses deep, highly conflicted emotions, because it means different things to different people. To those who favor the wall, it taps deep yearnings for security in a world filled with perceived physical, emotional, social and spiritual dangers. The wall promises safety, even salvation, to those who fear that multiculturalism could dilute our national purity — whatever that is.

The fact is, we are all being invaded by overwhelming forces — too much information, economic pressures, and deep fears of loss of status and privilege. All of this can be projected onto the invading horde from the south. The wall offers symbolic protection, securing our physical, social and economic wellbeing.

For others, the symbolic wall activates opposite emotions. It is experienced as the deepest violation of who we are, as a people, and of those who seek a better future in the U.S. It obstructs our ability to embrace immigrants who bring vitality, energy, and renewal to our multicultural society. It violates our values of freedom, difference and goodwill for humanity. For those of us who oppose the wall, it is a symbol of tyranny, oppression and monolithic vanity, evoking shame and outrage about what we are becoming. These conflicting meanings and emotions can be triggered simply by the mention of the single four-letter word: “wall.”

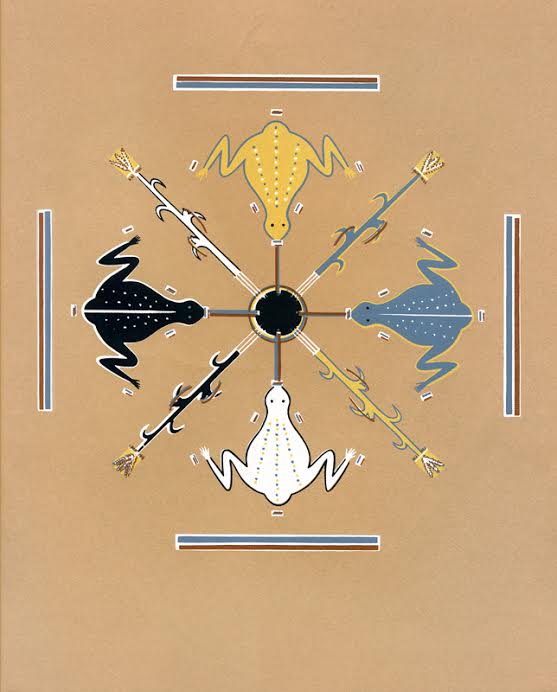

For those who hate Trump’s wall, it may be well to remember that for many, including the Tibetan Buddhists who know as much about the inner spiritual world as anyone, walls can protect what is most precious and vulnerable, as in their sacred paintings.

Similarly, I imagine that, for those who favor Trump’s wall, it symbolizes protection of the most precious and vulnerable aspects of American life. For those who love the wall, it would be well to remember that walls — symbolic or real — can segregate, traumatize and foment hatred and division.

It seems abundantly clear that the multiple meanings and powerful emotions of the symbolic wall have been politically manipulated and orchestrated to divide the country and to literally shut down the government. Such is the power of symbols to move people, to divide people and to unite people in other circumstances. We are being blocked — psychically, emotionally and legislatively — by this very potent symbol. Our leaders and we, as citizens, would do well to discuss all that the wall symbolizes. Only then might we dismantle the barriers between us to move forward as a nation.

Thomas Singer is a Jungian analyst, President of National ARAS and cofounder of Mindofstate.com. A further discussion of “the wall as a symbol” can be heard here.

Contents

Become a Member of ARAS!

Become a member of ARAS Online and you'll receive free, unlimited use of the entire archive of 17,000 images and 20,000 pages of commentary any time you wish—at home, in your office, or wherever you take your computer.

The entire contents of three magnificent ARAS books: An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, The Body and The Book of Symbols are included in the archive. These books cost $330 when purchased on their own.

You can join ARAS Online instantly and search the archive immediately. If you have questions, please call (212) 697-3480 or email info@aras.org

We Value Your Ideas

As our newsletter grows to cover both the ARAS archive and the broad world of art and psyche, we're eager to have your suggestions and thoughts on how to improve it. Please send your comments to info@aras.org. We look forward to your input and will reply to every message.

Subscribe

If you're not already a subscriber and would like to receive subsequent issues of this newsletter by email at no cost, e-mail us at newsletter@aras.org.