ARAS Connections

Image and Archetype

Welcome

by Tom Singer

At the heart of ARAS is the symbolic image and the mythopoetic imagination that is the source of the image and is nourished by the image. What can images offer us when our world is being turned upside down? Hopefully, we let them inform us with their wisdom and agony of the beauty and horror in the world.

My work over the decades in trying to understand the multiple ways in which cultural complexes express themselves—in politics, in psychology, in religion, in economics—has taught me that it can be hazardous to speak out when the collective psyche is inflamed. Highly charged emotions are instantaneously triggered and discharged. Black and white ideas couple with righteous judgements to replace any subtleties of reflection or measured understanding. The traumatic history of groups insures that only selective memories favoring a particular narrative surface that tend to filter all current events through their lens. Recently, the Presidents of Harvard, Penn, and MIT have all been caught in the brutal cauldron of trying to address the horrific and highly charged conflict between Palestine and Israel. It is dangerous but essential to address this conflict because it is so explosively violent in every way. Some like to exploit such conflict to promote further division while others mourn and search for healing. Some seek vengeance because their trauma is beyond imagination.

In this edition of ARAS Connections, Naomi Lowinsky gives passionate testimony in “The Muse of the Promised Land” to her multilayered response to the war in Palestine/Israel. Her words speak from her personal, cultural, and archetypal experiences of what is almost beyond words. And, it is the images that help ground her words in our essential humanity. Naomi writes:

I am flooded with the agony of the moment. My moral compass keeps spinning. My heart hurts for the Palestinians in Gaza who are being brutally bombarded day after day. They have no bomb shelters. My heart hurts for the mother in Jerusalem whose beautiful 23 year old son was at that music festival. His left arm was blown off by a grenade attack before he was taken hostage. Is he alive? My heart hurts for the mother in Gaza City, where the siege of Israeli bombing has begun. How can she find food and water for her little ones, without risking her life? Israel has stopped the transport of food, water, fuel and electricity. How will she and her little ones survive? My heart hurts for Tony Blinken, our American Secretary of State, who has a Shoah history much like mine. His grandfather fled from Russian pogroms. His stepfather survived Auschwitz and Dachau. He’s engaged in indefatigable shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East, trying to calm the fevers of war. He too must be in a trauma vortex.

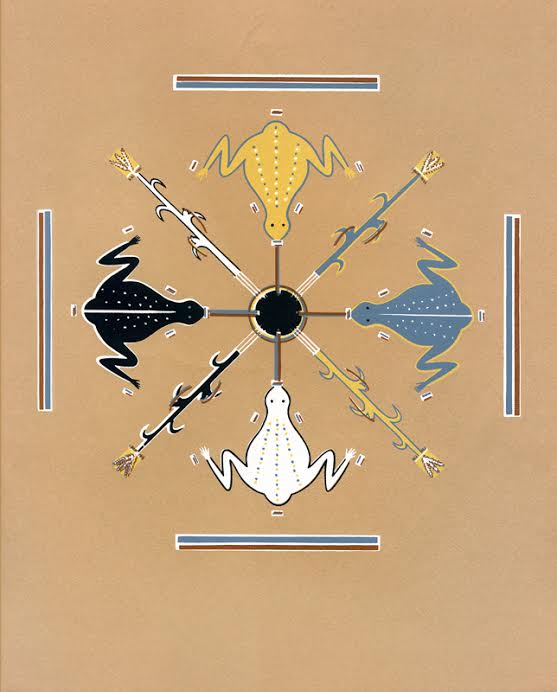

After reading about Naomi Lowinsky’s “spinning moral compass” that speaks to everyone grappling with the uncertainty of a conflict about which so many seem certain, the transition to Joseph Henderson’s musing in “On Creation Myths” about the nature of infinity as a young person may seem strangely comforting. How do we make sense of any of creation and all of creation when it confronts us with so many mysteries—wonderful and awful—that defy our capacity to understand? Once again, the symbolic image brings us closer to the mythopoetic imagination that attempts to conceive of what is beyond comprehension.

Sometimes we fish a bit to find a meaningful link between the articles in a particular edition of ARAS Connections. In this edition it hardly seems to be too much of a stretch to suggest that we are exploring through symbolic imagery the interconnected themes of destruction and creation in the world.

The Muse of the Promised Land

by Naomi Ruth Lowinsky

A Dream of Jerusalem

Jerusalem sits in mourning. She’s sitting shiva.

—Yehuda Amichai Open Close Open p. 136.

This piece was inspired by a dream:

I am in Jerusalem, standing among others outside an imposing structure—part city hall, part synagogue. But this is not a sanctuary for the living. It reverberates with spirits who seem trapped within it. They lament and they clamor. They beat their spectral heads and hands against the walls and windows, demanding the Jerusalem we always said we would return to, next year—as part of the Passover ritual. It is as though the building itself is possessed—writhing in an agony of dead Jewish souls. This almost living being is trying to contain the torment, the longing, the sorrow, the rage of generations of ancestors railing at the living, demanding the Jerusalem of their souls. My paternal grandparents, who died in the Shoah, tug at me, as though they want to join those inhabiting “The City of God,” a protest tent city that sprang up after tens of thousands of Israelis hiked in 95 degree heat from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem to protest Netanyahu’s Judicial Coup. One sign reads: “Bibi, haven’t the Jews suffered enough?” This cacophony of suffering invoked in me the Muse of the Promised Land—that shining angel of hope in Jewish history—which seems to lurch from catastrophe to miracle and back. But history had other plans.

Read The Muse of the Promised Land in its entirety here.

On Creation Myths

by Joseph L. Henderson, M.D. in collaboration with Daniel Benveniste, Ph.D.

In his introduction, Dr. Henderson explained that while creation myths ostensibly tell the story of the creation of the world and human life, they are, to a great extent, metaphors of the creation of consciousness. He began his presentation with a discussion of his personal relation to the topic.

"When I was young, in late childhood and early teens, I had an occasional attack of fear. I was afraid of infinity. Space for me was linear. It extended out in all directions from where I was and I tried to accept that it had no end. This was frightening. Surely there must be an end to it, I thought, some stone wall or mountain perhaps. But then the awful thought would haunt me that there was still space on the other side of this barrier extending off into infinity. So, my existential nightmare seemed to have no end any more than infinity has an end. Like many other young people, I managed to forget or at least repress my fear. But it laid there as an unanswered question, a mystery, for many years to come. Some time in my 20s I learned that modern physics and astronomy had some new ideas about the nature of space. From Arthur Stanley Eddington I learned that astronomical space was perhaps not linear but circular. This meant that if one had a strong enough telescope pointing into the sky one might see the back of one's own head. This was immensely consoling and relieved my fear of linear infinity. I realized then, that I had been a victim of Euclidean geometry and could now be free to explore the wonders of modern science." (JLH)

Read On Creation Myths in its entirety here.