ARAS Connections: Image and Archetype - 2015 Issue 3

For most, reading Jung is both exciting and challenging. His wisdom has brought the inner world back into the equation of how we know things and how we can live in the world. But, I suspect that for many, as for me, it has been equally challenging to remember, locate or research what Jung had to say about all sorts of important topics. I was lucky enough to have John Beebe as a generous colleague and every time I wanted to know what Jung had to say about a topic I could call on John to provide me with the relevant reference. But, most of us don’t have access to those rare individuals who seem to have such information at their fingertips. Now we all have such an encyclopedic reference tool at our fingertips in the form of the new Concordance that ARAS has just made available on our site. This Concordance is a boon to our tradition in that it permits instant access to Jung’s thoughts and quotes on everything he wrote in the Collected Works.

The creation of the Concordance is a major achievement and is due almost single-handedly to the work of Thornton Ladd who bequeathed it in his estate to ARAS on the condition that it be made available to all at no cost. Thornton Ladd dedicated his considerable intelligence, talent, energy, time and money to the creation of the Concordance. An early board member of National ARAS who, with a visionary’s eye, saw the potential of the computer to bring the Concordance into being. He had the vision several decades before it could be fully realized because of the numerous technical and legal hurdles that needed to be overcome. Unbelievable persistence and dedication are at the heart of his creation. It is with a great sense of honor that we now bring to the world the fulfillment of Thornton Ladd’s vision in this Concordance to Jung’s Collected Works. Use it, enjoy it, marvel at it, and let us know what you think about it.

Interview with Chester Arnold - Part One

In this inspiring dialogue between the painter Chester Arnold and Tom Singer several other layers of fruitful dialogues appear – those between Chester Arnold and his students, between his exploration of the real world and the interior creative realm and as a constant throughout his work, the visual dialogue between his art and human history. Arnold’s work is currently part of a travelling museum exhibition, Environmental Impact, which opened at The Canton Museum in 2013 and continues to tour across the US through 2015.

-Ami Ronnberg

Tom Singer (TS): It looks like you’re deep into an excavation right now. [Figure 1]

Chester Arnold (CA): It’s a subject that I’ve worked on periodically… Probably the longest and most sustained period of so called excavation paintings was in 1983-84. It started when I was flying on a trip to Boston. In the flight magazine there was a photograph about the size of a postage stamp of some dig in Africa and there was a man in a white suit with a panama hat standing over the ground looking at a hole and I thought to myself “That’s such rich material, I’ve got to do a painting” because I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I’ve always loved imaging space from slightly elevated point of view because of the kinds of aesthetic structures that emerge in those perspectives when you’re interpreting or imagining a space. So I just started carving excavations into these little imaginary planes and what emerged was all kinds of unexpected things. I started to imagine excavations of… ancient things, modern things and future things.

This was during the Reagan years in which one never knew when a button could actually be pushed and civilization would be reduced to that little Anthropocene layer of 88 million years ago.

That was a pretty rich territory for me to explore…anyway this new painting [Figure 1] is another painting in that series. Because of the scale of this new canvas, the invitation was to dig broader and deeper and change the scale to make it more vast and that appealed to me too. There are so many factors that go into making images originally…you know I have this lecture that I give my students and it’s a chart [Figure 3] which I devised in a sketch book that has a series of concentric circles and in the center of this universe of concentric circles is the “primal artist”, the child, the creative impulse…which, in my view, everybody is born with a certain amount or charge of.

And I saw that as my kids were growing up that they had very vivid imaginations and were motivated and inspired to make things all the time -- as I recall, I was too as a child -- and then slowly through school, other disciplines start to be overlaid on consciousness and then eventually that part of the brain—whether neurologically or just sociologically-- that creative part is forced into a corner in most cases unless there are parents who really encourage it or unless the impulse is so strong that it’s irresistible. So, my students, a lot of them--the older ones especially-- come in broken down in that sense, from originally having had some artistic experience earlier in their lives when someone either insulted them or they had a teacher who said ‘No, you’re no good. You should do something else.’ That turned a switch off in that creative impulse and so my job is to turn it back on because I think it’s still in there and I’ve found that it still is with a certain amount of support. So, in the center of that universe is that “primal artist” with the individual creative fire…and the next level is the realm of friends and peers and family which is the world that the creative effort is shared with first. And then the world beyond that, the concerns beyond that become education, college and then each ring moves further and further out to a professional career. The last universal ring is eternity and the world beyond us, history beyond us.

Read An Interview with Chester Arnold in its entirety.

Comics, Antiheroes and Taboo: Reflections on the Edge of Pop Culture

The author is currently a PhD student in Psychoanalytic Studies at Essex University. From Brazil, she graduated in advertising (ESPM, SP, 1987), and holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology (UNIP, SP, 1997) and a master’s degree in sciences of religion (PUC, SP, 2003).

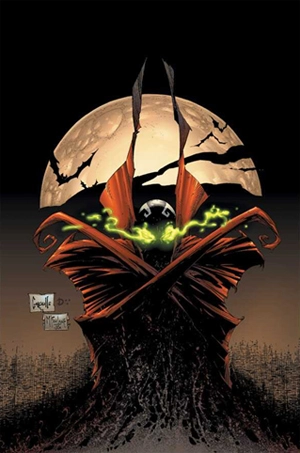

This article analyzes the comic book series Spawn, by the Canadian Todd McFarlane, in an exploration of and attempt to give voice to neglected cultural aspects of the American society and western collective shadow, and how they are translated by this American antihero. As I see it, the character Spawn symbolizes and reflects the putrefying process of a sociocultural body and represents an effort to give birth to a new system of beliefs and values in the contemporary secular world. I use extracts from the text of the comic book series to present some of my findings and reflections about this controversial antihero, as well as to provide further insights into the challenging times we live in.

Keywords: shadow, death, scapegoat, comic books, antiheroes, popular culture, myth.

I. Introduction

In 1998, while I was in Brazil concluding a specialization course in Jung’s psychology, I decided that I wanted to work with the scapegoat phenomena, but I didn’t know yet how to approach it. Then I was attracted by the advertising of the movie Spawn1, about a comic-book superhero, whom I had never heard of. That same night I had a dream about that strange superhero. My curiosity was then fully engaged, so I decided to watch the movie. What I saw perplexed me: how could a semi-dead, festering, depressive, dense, complicated superhero be so popular among young teenagers in the universe of American comics, competing side by side with the classic superheroes like Superman, Batman, Spiderman, and Wolverine?

In fact, 'antiheroes' similar to Spawn have always populated literature, movies, and many other comic books2, but for many reasons that I will bring forth and discuss in this article, I chose Spawn as a major and 'super' complex example of how a comic books antihero, can embody multiple layers of psychological interpretation. From the beginning of my research, I was impressed by how much a fictional character coming from a pop form of mass communication could be so deeply connected with archaic and shadowy aspects of our human condition.

Read Comics, Antiheroes and Taboo: Reflections on the Edge of Pop Culture in its entirety.

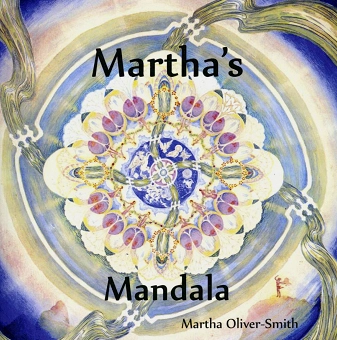

Martha's Mandala Review

This story is filled with the charm and nostalgia of a time gone by, a time from the 1920’s to the 1950’s; but these stories also contain episodes of great suffering and trauma untreated and unacknowledged except through the painting of mandalas which offer calm and solace to the author’s grandmother Martha Stingham Bacon (known as Patty) who paints these images and quietly keeps them in a small room in the family home called the Acorns in Peace Dale, RI. At times it is hard to tell who the protagonist in this book is ---Patty, the author Martha Oliver-Smith (named for her grandmother), the mandala itself, or even C. G. Jung whose life and work touched this family in deep ways. From the image and the text we might say that the mandala has an aliveness, a psychoid or “psyche–like” quality that gives it power and a living presence for the grandmother and grandaughter especially through hard times. It is a physical/spiritual touchstone that symbolizes a higher self. (Caption under mandala above: Martha’s Mandala by Martha Stingham Bacon, ca. 1940)

In 1922, Patty was overcome by a “tidal wave,” was hearing voices with wishes to kill her children and was psychiatrically hospitalized. At the time she had three young daughters Martha (called Marnie and the author’s mother) who was six, Helen, aged four and Alice was the youngest at age two. In addition, she was caring for her widowed mother and her dependent sister Harriet. Patty’s husband Leonard was working as a university professor and he eventually became Pullitzer Prize winning poet in 1940. As reported by the author and from the excerpts of Patty’s writings, the psychiatric treatment available at that time did not help. The voices did not stop but neither did her writing and drawing. An introvert, she kept these life-sustaining activities to herself. Leonard, also a writer, was an extravert and the life of the party.

Read this review in its entirety here.

The Poetry Portal

The symbolism of veil and veiling is rich - the veil as covering, hiding or protecting. Revealing can be seen as unveiling. In many traditions, the ordinary world is seen through a veil, hiding the true reality. The sacred is hidden from view by a veil as were the ancient gods or goddesses. This beautiful abstract image painted on a veil was done by Marina Kiesling as part of the second ARAS Pioneer Teens summer program where the teens explored a symbol of their choice for two weeks, which resulted in a final art work. We hope that this image will inspire you to write a poem in our Ekphrasis tradition. Please send your poems to info@aras.org by November 15th.

We thank everyone who submitted a poem that was inspired by the "Unknown Road" image in our last issue. The poems are available to read here.

Contents

Become a Member of ARAS!

Become a member of ARAS Online and you'll receive free, unlimited use of the entire archive of 17,000 images and 20,000 pages of commentary any time you wish—at home, in your office, or wherever you take your computer.

The entire contents of three magnificent ARAS books: An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, The Body and The Book of Symbols are included in the archive. These books cost $330 when purchased on their own.

You can join ARAS Online instantly and search the archive immediately. If you have questions, please call (212) 697-3480 or email info@aras.org

We Value Your Ideas

As our newsletter grows to cover both the ARAS archive and the broad world of art and psyche, we're eager to have your suggestions and thoughts on how to improve it. Please send your comments to info@aras.org. We look forward to your input and will reply to every message.

Subscribe

If you're not already a subscriber and would like to receive subsequent issues of this newsletter by email at no cost, e-mail us at newsletter@aras.org.