Chapter 5: ORPHEUS REMEMBERED

Jules Cashford

Figure 5.1 Orpheus playing to entranced Thracians, with their fox-skin caps and long heavy embroidered cloaks. Orpheus, by contrast, is dressed as a Greek. His left hand has the look of a bird with outstretched feathers, singing as he plays. 440 BCE. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

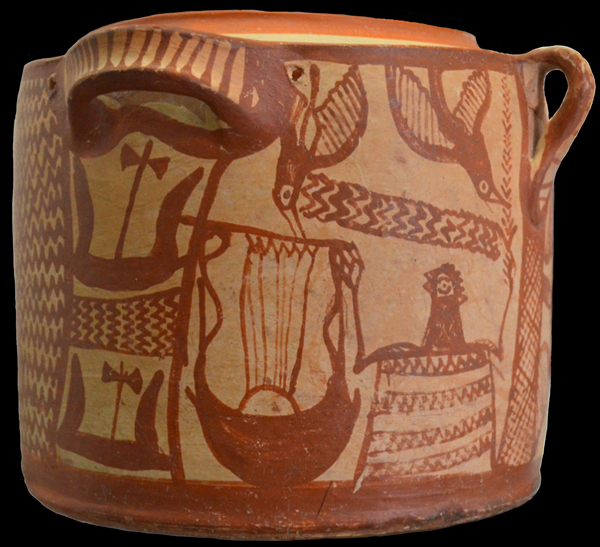

Figure 5.2 Lyre player from Kalami enchanting birds. c. 1300 BCE. Late Minoan IIIB. Museum of Chania. The singer is often called Orpheus or Apollo, though only Apollo appears in Mycenaean Linear B script from Knossos under the name Paean. Bulls’ horns with the double axe between them are a Minoan image of wholeness.

Figure 5.3 Mnemosyne, standing, holds the scroll of Memory, looking down upon her first-born daughter, Kalliope, She of the Beautiful Voice, who plays the lyre without looking at her mother, as though she is playing the song inscribed in her mother’s scroll, knowing it by heart. Fifth-century BCE. Lekythos, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Siracusa.

Figure 5.4 The scribe Nebmeroutef and the god Thoth in his baboon form. Schicht statue. 1391–1353 BCE. The Louvre.

Figure 5.5 Asklepios and his snake healing the dreamer of the wound on his shoulder. Both snake and god touch the same place, suggesting that healing arises from a union of body and soul. Archinos, the name of the dreamer, wrote his gratitude at his cure on the rectangular plaque on the wall above him, ritually left empty so the dream could come. Votive plaque dedicated by Archinos, the dreamer. c. 380 BCE. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Figure 5.6 Apollo with his lyre dancing with the Muses—“Apollo Mousagetes.” The sun below the horizon shows that it is winter, when Apollo leaves Delphi and goes north, to the land of the Hyperboreans, beyond the North Wind, and Dionysos takes over the rulership of Delphi. The serpentine rivulets of water suggest rain. c. 750 BCE. Staatliche Kunstsammlung, Dresden.

Figure 5.7 The Muse Klio, later known as the Muse of History, reading from her scroll. Attic red-figure Lekythos, c. 430 BCE, Boeotia.

Figure 5.8 Kalliope holding out the lyre to Apollo who is approaching her ritually, holding his laurel staff between them. c. 430 BCE. Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich.

Figure 5.9 Hermes, the Messenger, with lyre and caduceus. c. 450 BCE. The British Museum.

Figure 5.10 Orpheus playing the lyre between two Thracians holding spears. c. 430 BCE. British Museum.

Figure 5.11 Orpheus, on the right, dressed unusually in a peaked Thracian cap, holding his lyre in his left hand, bringing Eurydice out of Hades, with Hermes on the left. They are both tenderly touching Eurydice, who is veiled, the central figure and the visual focus of the composition. This is the moment when Orpheus turns to look back for Eurydice, and Hermes lays his hand gently on her arm to take her back down to the underworld. The figures of Orpheus and Hermes are almost a mirror image of each other: Orpheus with his arm raised to clasp the hand of Eurydice, who is brushing his shoulder as if to comfort him, while the downward gesture of Hermes draws her back. Marble relief. 420 BCE. The Louvre.

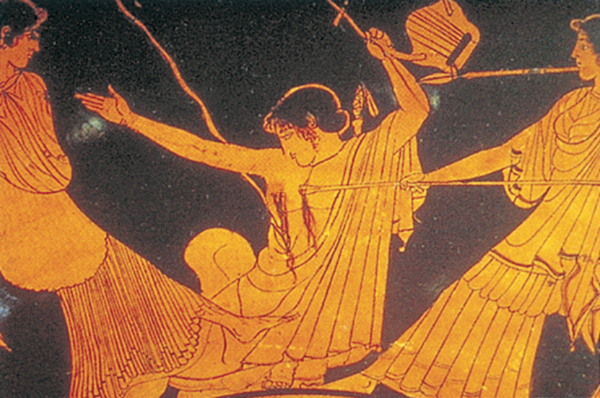

Figure 5.12 Orpheus dismembered by Maenads. Painted dish by the Louvre Painter. 480–470 BCE. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Figure 5.13 Maenad slaying Orpheus. Lekythos. c. 450–440 BCE. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Figure 5.14 Maenad severing the head of Orpheus. Red figure vase painting. 480 BCE. Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothéque Nationale.

Figure 5.15 Orpheus singing with oracular voice to a young man who is taking it down with a stylus and tablet. Apollo, with his commanding gesture, is telling the singing to stop, demanding his godly powers back from him. Red-figure vessel. 410 BCE. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Figure 5.16 Dionysos dancing with his Maenads. 490 BCE. Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Figure 5.17 Orpheus playing his lyre (closeup of Figure 1). The wreath of ivy leaves round his head is evocative of Dionysos rather than Apollo, whose leaves were of laurel.

Figure 5.18 The Pet-e-lia Tablet from Italy. c. 300–200 BCE. British Museum. The case in which the tablet is enclosed is Roman, 500 years later than the tablet itself.

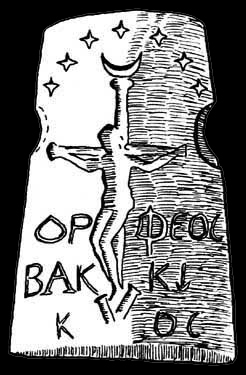

Figure 5.19 Jesus as one with Orpheos Bakkikos, with the Crescent Moon of Rebirth as the crown of the cross, and the seven stars of the Pleiades, the Lyre of Orpheus, arching over him above. The syncretic feeling is one of joy. Cylinder seal, c. 300 CE.

Figure 5.20 Arte romana. 200–250 CE. Mosaico pavimentale, marmo, 150 × 150 cm. Palermo, Museo Archeologico.

Figure 5.21 Either Orpheus is still enchanting wild animals or “Orpheus” is serving as an allegory of Christ taming the wild hearts of the pagans. Different people saw different things. Marble table support from Asia Minor. Late fourth century. Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens.

Figure 5.22 Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, daughter of the Roman Emperor Theodosius. Fifth century, Ravenna.

Figure 5.23 The Poet waiting for the Muse, with the empty scroll before him. The eleventh-century Dutch/German Poet Hendrik van der Veldeke. Codex Manesse. 1305–35. Heidelberg University Library.

Go back to When the Soul Remembers Itself: Ancient Greece, Modern Psyche