by Torben Gronning, Patricia Sohl and Thomas Singer

Visual Resources Vol. XXIII, No. 3, September 2007, pp. 245-267

This article describes the history of the recently digitized and online accessible Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARAS), from its 1930s origins at the famous Eranos annual conferences of eminent scholars in Ascona, Switzerland to the present. The purpose, function and structure of the collection are explained and illustrated with an example. ARAS is compared with other art image databases, and its unique features are elucidated. The article argues that the heritage and focused purpose of ARAS has allowed it to successfully address common iconographic challenges and that the online resource (www.aras.org) adds important new dimensions to the user experience.

Keywords: Iconography; archetypal symbolism; cross-cultural symbols; Fröbe-Kapteyn, Olga (1881-1962); Jung, Carl Gustav (1875-1961).

Introduction

When a filmmaker needed inspiration for her award-winning animated film, she found it in the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism. When a theater director looked for ideas for sets and costumes, he consulted the archive, as did an artist developing a survey of masks throughout world history and a theologian looking for an androgynous figure of Christ. Numerous analytical psychologists and psychotherapists regularly consult the archive to explore their own and their clients' dreams by analyzing the symbolic imagery of these dreams in a process of self-discovery.

The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism, often just called ARAS, has a most interesting history, rooted in the Eranos meetings of the early 1930s, when world-renowned scholars from many fields gathered for discussions that touched on the history of religion, the history of art, anthropology, psychology, sociology and archaeology. Images to illustrate the topics of these cross-disciplinary meetings formed the beginning of the ARAS archive, and the Eranos heritage became the foundation for developing the nomenclature used in ARAS's image classification.

ARAS has since developed into a rich collection of 17,000 annotated photographic images of human creative expression, purposefully selected from every culture, spanning the 30,000 years of human history since the Ice Age. With its cultural, historical, anthropological and psychological commentary, ARAS has become over time a unique tool for academics, researchers, scholars, artists, writers, historians, anthropologists, analytical psychologists, psychotherapists, students, and the general public alike.

Early History of ARAS and Eranos

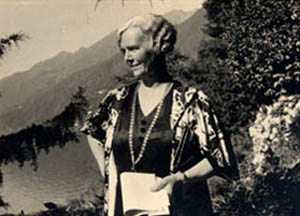

The conception of ARAS dates back to the 1930s and is intrinsically linked to the Eranos Society and its creator, Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn (Figure 1). She was born in 1881 of Dutch parents in London where her father Albert Kapteyn, an avid photographer, was the director of the Westinghouse Brake and Signal Company. Her mother was a philosophical anarchist, a writer on social questions, and a friend of playwright George Bernard Shaw and anarchist Prince Kropotkin. Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn studied applied art in Zürich and helped in her father's darkroom. She became a young widow when her husband Iwan Fröbe, the Austrian musician, was killed in a plane crash in 1915 while testing an aerial camera for the Austrian army. She had twin daughters, born after the death of her husband.1

Figure 1 Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn in the 1930s. Photograph by Margarethe Fellerer. Courtesy of Eranos Foundation Archives, Ascona-Moscia, Switzerland |

Around 1920, Olga Fröbe and her father went for a recreational stay to the Monte Verita sanatorium in the Swiss village of Ascona, located on the western bank of Lake Maggiore, a setting of great natural beauty looking south into Italy. Ascona had since the late nineteenth century developed into a gathering place for artists, writers, dancers, political radicals, utopians and gurus, including Lenin, Trotsky, Mikhail Bakunin, Prince Kropotkin, Hermann Hesse, Stefan George, Rudolf Steiner, Mary Wigman, Isadora Duncan, Hans Arp, Paul Klee, Emil Jannings, Emil Ludwig, and Erich-Maria Remarque. Albert Kapteyn bought a house overlooking the lake, Casa Gabriella (Figure 2), for his daughter and provided funding for her to live in reasonable comfort.

Olga Fröbe's great interest was spiritual research, and she built a lecture hall and a guesthouse on her grounds in 1928. After a short and unsuccessful attempt at running a school for spiritual research, she developed the idea of founding a meeting place for East and West. In 1932 she went to Marburg to visit Rudolf Otto, the prominent German theologian, scholar of mysticism and comparativist of Eastern and Western religions. Otto was very receptive to her plan for a lecture program and proposed the name "Eranos," which in Greek means a shared feast.

For the next sixty-six years this annual lecture program, begun in August 1933 and called the "Eranos Tagungen" (Eranos meetings), would assemble many of Europe's leading intellectuals in Ascona to give scholarly lectures about their latest insights in the fields of religion, philosophy, history, art and science. The imaginative and inspiring forceof mind and the unfailing rigor of scholarship2 brought forward ideas often "on the edge."3 The lectures were published after each year's conference in the Eranos- Jahrbuch (Eranos Yearbook).4 Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn was the publisher of each Eranos yearbook from 1933 to 1961, the year before her death. Six volumes of selected Eranos lectures, translated into English and edited by Joseph Campbell, were published in 1954-1968 as part of the Bollingen Series.5

Figure 2 Casa Gabriella, Ascona, Switzerland in the 1950s. Photograph by Margarethe Fellerer. Courtesy of Eranos Foundation Archives, Ascona-Moscia, Switzerland. Archetypal Symbolism and Images 247. |

The subject of the first two-week Eranos conference in 1933 was "Yoga and Meditation in East and West," held in the lecture hall now named "Casa Eranos." Among the speakers were the scholars of Indian art and religion Heinrich Zimmer and G.R. Heyer, the Buddhist scholar Caroline Rhys Davids and the Sinologist Erwin Rousselle.6

Psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology Carl Gustav Jung (Figure 3), reluctant at first, decided to participate when he saw the lecturer list and realized that "those are all my friends!"7 Jung would become a regular contributor each year to the two-week conference in late August. Jung remained a fundamental figure in the organization of the conferences due to the fertile influence of his analytical psychology-referred to as a "spiritus rector" by Eliade in 1955. Althoughthe symposia were not "Jungian," they focused on the core idea of "archetypes" in human life.8

Figure 3 Carl Gustav Jung in the late 1940s. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Thomas B. Kirsch, MD, Palo Alto, CA. |

Despite the difficulties of the pre-war years, the Eranos conferences took place without interruption. Planning for next year's conference would begin as soon as one year's conference was over. Olga Fröbe was the impresario and organizer, although she insisted that Eranos was without plan or program. She decided the theme, invited the speakers, organized the announcements and printing of programs, booked accommodations, planned catered lunches and dinners, made traffic arrangements with local authorities.

A conference typically included anywhere from seven to twelve half-day lectures, delivered in German, French or English, and attended by up to two hundred persons. The afternoons were open for informal discussions, sailing on the lake, excursions in the area or reading. An equal representation of first-time speakers and speakers with previous Eranos experience assured renewal and continuity through the years.

The scholars from the early years and their expertise demonstrate the cross-cultural nature of the Eranos experience: Heinrich Zimmer (Indian religious art), Károly Kerényi (Greek mythology), Mircea Eliade (history of religions), Jung and Erich Neumann (analytical psychology), Gilles Quispel (Gnostic studies), Gershom Scholem (Jewish mysticism), Henry Corbin (Islamic religion), Adolf Portmann (biology), Herbert Read (art history), Max Knoll (physics) and Joseph Campbell (comparative mythology).9

Olga Fröbe had a lively interest in finding and collecting images to illustrate the topic of each year's meeting, which in addition to the first year's "Yoga and Meditation in East and West" (1933) included such titles as "The Gestalt and Cult of the Great Mother" (1938), "The Hermetic Principle in Mythology, Gnosis, and Alchemy" (1942), "The Mysteries" (1944), "Spirit and Nature" (1946) and "Man and Time" (1951).10

In 1935 she systematically began to collect pictures that exemplified archetypal themes as a complement to Jung's writings. She later explained that "Those who feel the truth of the old Chinese conception that all that happens in the visible world is the expression of ideas or images in the invisible might do well to consider Eranos from that point of view." She traveled to the great libraries in Athens, Rome, Paris, London and elsewhere in Europe, finding and purchasing photographs of ancient frescoes and other paintings, sculpture, manuscript illumination and primitive folk art. These she classified according to archetypal themes in what became known as the "Eranos Archive," located for want of other space in her bedroom at Casa Gabriella.11

The 1938 Eranos conference on "The Great Mother" included an exhibition of large photographs from the Eranos Archive (Figure 4). Hildegard Nagel took the pictures back for an exhibition at the Analytical Psychology Club in New York, thus facilitating Eranos' debut in America.12 The exhibited pictures later became the basis of Erich Neumann's book The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype (New York: Pantheon, 1955). Figures 5, 6 and 7 show expressions of the Great Mother archetype from three different cultures and time periods.

With financial assistance from benefactors Mary and Paul Mellon of Pittsburgh, both deeply involved in Eranos and later the founders of the Bollingen Foundation Archetypal Symbolism and Images 249 created to assure a wider audience for Jung's work,13 Olga Fröbe traveled to Rome in 1938 to obtain photos of an illuminated manuscript of the Divine Comedy kept in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana Library.14 She wrote to Mary Mellon that she was "going to collect every archetypal representation I can find, ... [e.g.] the Crucifixion, the Baptism, the Descent into Hell, the Resurrection, the fight with the Dragon." She continued to Amsterdam, London, Paris, Bonn, Trier and Berlin, "picture-hunting everywhere."15

At the start of the Second World War, Olga Fröbe was contemplating what to do with her Eranos archive. She learned of the Warburg Institute - moved in 1934 to London from Hamburg because of the Nazi danger - and its library, which seemed a good fit for her collection. After the war, in 1946, she began to send her photographs to London, and in 1956 the Warburg Institute accepted her entire collection. She gave photographic duplicates of the archive (made at Bollingen expense) to Jung (who shortly before his death gave it to the Jung Institute in Zürich) and to the Bollingen Foundation in New York, which was, at that time, supporting numerous scholars in their quest for the meaning of symbolism and publishing the works of Jung.16

Jessie E. Fraser, Librarian of the Analytical Psychology Club in New York, was entrusted with editing and cataloging the archive. In 1959, her proposal for a cataloging scheme found support with members of the Eranos Conference, and the Bollingen Foundation decided to make the archive a special project and increase their grant.17 In 1960, the archive was renamed the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARAS), reflecting the many additions to the original Eranos collection.

Figure 4 Swiss journalist and publicist Fritz René Allemann viewing the Eranos Archive in 1939, featuring archetypal representations related to the process of rebirth. (The Eranos Conference 1939 was entitled "The Concept of Rebirth in the Cults and Religions of Various Times and Peoples.") Photograph by Margarethe Fellerer. Courtesy of Eranos Foundation Archives, Ascona-Moscia, Switzerland. |

In the development of keywords to reflect archetypal themes, Jessie Fraser collaborated with analytical psychologist Joseph L. Henderson in San Francisco, who worked with Jung and wrote a chapter in Man and His Symbols.18

In 1969, the Bollingen Foundation gave ARAS to the C.G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology in New York, who undertook a ten-year development project funded by Jane Abbott Pratt and the Frances G. Wickes Foundation. The archive grew and had, in 1977, reached 25,000 representations, of which 12,000 were mounted, numbered and in various stages of completion and 8,000 finished.19 Copies of the collection were housed at the C. G. Jung Institutes in San Francisco and Los Angeles. These three Jungian centers are the founding members of National ARAS.

The Bingham Foundation and many other donors were instrumental in supporting the continued expansion of the collection in the 1980s, and also made possible the writing and publication of two scholarly volumes, Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism I-II, based on approximately 200 selected images from ARAS.20

Figure 5 The Goddess Ninhursag ("Lady of Birth") c.2017-1763 BC. Terracotta, 10.2 cm high. Origin: Babylonian Period, Return of Amorites to Babylonia, Time of Isin and Larsa Dynasties. Provenance: Iraq. ARAS Record 2Bh.004. Repository: Iraq Museum, IM 9574, Baghdad, Iraq. |

In 2003-04, the New York collection of 17,000 images and 20,000 text commentaries was scanned. About 45,000 catalog cards from the New York and San Francisco collections, which had continued its own further development since the early 1980s, were combined to produce 10,000 different keyword-based archetypal themes. Private donors funded this large project that ultimately resulted in ARAS becoming available as an online subscription-based resource (www.aras.org) in 2005.

Purpose of ARAS: Use and Amplification of Symbols and Images

Although the creation of the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism was motivated by Jung's discovery and description of the "archetype," the use of ARAS goes well beyond Jungian psychology. However, ARAS owes a tremendous debt to Jung's basic idea of archetypes and the collective unconscious. Jung was the particular proponent of a broadly archetypal point of view that insists upon common human or transpersonal and symbolic connections transcending cultural and theological boundaries.21

Figure 6 Minoan Deity or Worshipper. Terracotta. Origin: Pre-Hellenic Era, Crete, Post Palace Period, Late Minoan IIIa, b, c (Achaeans in Crete). ARAS Record 3Ce.002. Courtesy of Archeological Museum Herakleion, Crete, Greece. |

One might argue that from an iconographic classification point of view Jung's concepts have created the essential foundation for the nomenclature developed to categorize the ARAS image content. The term "archetype" means "original pattern from which copies are made," and it appeared in European texts as early as 1545. It derives from the Latin noun archetypum and from the Greek noun arkhetypon, meaning "pattern, model," and the adjective arkhetypos, meaning "firstmolded," from arkhe- ("first") + typos ("model, type, blow, mark of a blow").22

Jung explains how the collective unconscious-humankind's shared psychic foundation patterning all expressive endeavors-rests on "archetypes" or "primordial images" (CW 8: 229).23 Jung was not the first to discover and formulate this idea of the archetype. Anthony Stevens explains how Jung acknowledged his debt to Plato, describing archetypes as "active living dispositions, ideas in the Platonic sense, that perform and continually influence our thoughts and feelings and actions" (CW 8: 154).24

For Plato, "ideas" were mental forms superordinate to the objective world of phenomena. They were collective in the sense that they embody the general characteristics of groups of individuals rather than the specific peculiarities of one. Thus, a particular dog has qualities in common with all dogs (which enable us to classify it as a dog) as well as peculiarities of its own (which would enable its master to recognize it). So it is with the archetypes: they are common to all humankind, yet each person experiences them in a unique and personal way.

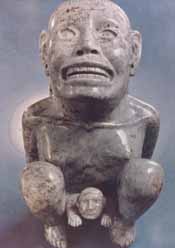

Figure 7 The Goddess Tlazolteotl. Aplite speckled with garnets, 20.2612 cm. Provenance: Mexico. Origin: Mexico, Aztec. ARAS Record 8Bd.017. # Dumbarton Oaks, Pre- Columbian Collection, Washington, DC. |

The German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) believed that his delight in scientific discovery was due to the mental exercise of matching ideas or images already implanted in his mind by God with external events perceived through his senses. Kepler's "inner ideas" that lie "under the veil of potentiality" and are "derived from a natural instinct and are inborn" are clearly akin to Jung's "primordial images."25 It is speculated that Jung may have been influenced in his thinking about archetypes by the German ethnologist Adolf Bastian (1826-1905), who studied the myths, folklore and customs of humankind all over the world. Bastian was impressed by the similarity, which existed between many of the themes and motifs he encountered wherever he went. He noticed, however, that these universal themes - which he called Elementargedanken (elementary ideas) - invariably manifested themselves in local forms peculiar to the group of people he happened to be studying: these he called Volksgedanken (ethnic ideas).26

Archetypes transcend culture, race and time. Thus, in Jung's view, the mental events experienced by every individual are determined not merely by personal history, but by the collective history of the species as a whole (biologically encoded in the collective unconscious), reaching back into the primordial mists of evolutionary time.27 Jung made it a point to distinguish between the archetype-as-such and the archetypal images, motifs and ideas, which the archetype gives rise. One cannot "see" the archetypes themselves-only their indirect manifestation in or as images, motifs and ideas associated with or stemming from the archetypes. In his writings, Jung explained archetypes in the following ways:

The term "archetype" is often misunderstood as meaning a certain definite mythological image or motif ... on the contrary, [it is] an inherited tendency [i.e., ability, potential] of the human mind to form representations of mythological motifs-representations that vary a great deal without losing their basic pattern. ... This inherited tendency is instinctive, like the specific impulse of nest-building, migration, etc. in birds. One finds these representations collectives practically everywhere, characterized by the same or similar motifs. They cannot be assigned to any particular time or region or race. They are without known origin, and they can reproduce themselves even where transmission through migration must be ruled out. (CW 18: 523; emphasis in original)

...besides [the intellect] there is a thinking in primordial images, in symbols which are older than the historical man, which are inborn in him from the earliest times, and, eternally living, outlasting all generations, still make up the groundwork of the human psyche. (CW 8: 794)

As the products of imagination are always in essence visual, their forms must, from the outset, have the character of images and moreover of typical images, which is why ... I call them "archetypes." (CW 11: 845)

...[Tribal] lore is concerned with archetypes that have been modified in a special way. Another well-known expression of the archetypes is myth and fairytale. (CW 9(1): 5,6)

It is the manifold expressions of these archetypal images and symbols that make up the ARAS collection. The collection probes the universality of archetypal themes and provides a testament to the deep and abiding connections that unite the disparate factions of the human family.

Harry Prochaska, who served as San Francisco ARAS's curator 1978-1992, defined "symbol amplification" as the elaboration of the historical and cultural matrices of a symbol in its variant forms so that one develops a larger sense of its polyvalences. This process is different from subjective association. Association stems from one's personal biography projected on to the symbol. In the associative process, symbolic meaning may be legitimately and absolutely personal, carrying a value, which no one else shares nor needs to share. Amplification, however, leads to significant clues which lie in the cultural unconscious, for each of us is born into a culture as well as into a family. Amplification and association are parallel pathways to symbolic meaning.28

Prochaska quotes Mircea Eliade who states that "The essential problem is to know what is revealed to us not by any particular version of a symbol, but by the whole of the symbolism."29

Circumambulation-"a walk around the image"-is a term used to describe the interpretation of an image by reflecting on it from different points of view. Circumambulation differs from free association in that it is circular, not linear. Where free association leads away from the original image, circumambulation stays close to it. Jung uses the term "circumambulation" in his commentary on The Secret of the Golden Flower,30 where he defines it as a "psychological circulation" or "movement in a circle around oneself" so that all sides of the personality become involved (CW 13: 38). In the mandala, Jung saw a uniting symbol or an archetype of wholeness.

German physicist and Nobel laureate Wolfgang Pauli (1900-1958) offered a related description of the creative method of scientific discovery, when he talked about "continuously taking up an issue, thinking about the object, then putting it back down again, then gathering new empirical material, and continuing this, if necessary, for years. In this way, the subconscious is stimulated by the conscious, and only in this way, if at all, can something come of it."31

The ARAS archive is especially useful to analytical psychologists and psychotherapists or anybody interested in amplifying images that emerge in dreams. The process begins when one is struck by a particular image, wondering why that particular image appeared and what it means. We do know that each image is carefully chosen by the psyche as a means of communicating specific information about the dreamer's state of development and attitude. One could say that the image is a key with the potential to unlock a particular door leading to greater knowledge or consciousness about the dreamer. ARAS gives the analyst or the dreamer a means of discerning which door the key fits. What is revealed through the study of the many visual examples of the images and their cultural, historical and psychological amplifications helps to enlarge our understanding of the symbolic image. And it is our relationship to the symbol that effects the deep change or transformation of our being.32

The use of the archive often begins with the decision to explore a particular image, whether the image originates from a dream, an idea to use in an artistic creation, a cultural study, a research paper or project, or simply to explore the richness of the archive. The search results in multiple examples that demonstrate how the same image is expressed in different times, cultures and mediums. It is this commonality that helps to distill the meaning of the image. The search may lead one off on various tangents, circling around the meaning, fleshing it out until one finally comes to an understanding of what it means. An excitement and enthusiasm often accompanies the search, carrying one along on a fascinating and enlightening journey through the world of symbolic images.33

The ARAS homepage (www.aras.org) illustrates this variety with two examples. One example shows the results of a search for the archetypal theme "lion";34 the other is an animated collage of images associated with the archetypal theme "snake on tree."35 Both examples let the user enjoy the full richness of the images on their own and discover how many cultures and eras have expressed a common idea, each in their own ways.

Ami Ronnberg, who in 1979 continued Jessie Fraser's work on the classification of the archive's images and became curator in 1984, describes how the interconnectedness of symbols often guides the imagination in the process of circumambulation: "Begin with a thread, follow a lead, look up similar ideas, and move intuitively around a symbol or a dream."36