ARAS Connections: Image and Archetype - 2012 Issue 3

People have been using stones to send messages to themselves, their gods, and future generations for aeons. In the late 1970's I was wandering through the Plaka, the old village-like section of Athens just beneath the Acropolis. I came across a strange little store with a window full of stones with human faces and animal forms that seemed to emerge from beneath the stone's surface and were highlighted. I walked in to see what was happening in this unusual place. A haggard, middle-aged woman sat behind a glass counter and I asked her about the store and its stones. She told me that her son had been part of the student uprising against the Greek Colonel's regime at the Athens Polytechnic in November, 1973. Dozens of students occupying the University were murdered when the Colonels sent a tank and armed troops through the gates. The shopkeeper's son was one of the students killed by the Colonels' soldiers. She described falling into a prolonged, profound depression in the grief over her lost son. One day she noticed a stone on the ground and saw a face in it. She picked it up and started collecting stones in which she saw figures that she would highlight. She recounted how she slowly came back to life by seeing life in the stones. She decided to open the store to memorialize her son and tell her story. The store, the stones, the woman, the story all seemed improbably moving to me. She came back to life as she rediscovered life in seemingly inanimate matter.

This edition of ARAS Connections features two fine articles that are linked through the symbolic life of stones in the human imagination. Ruth Breuer has written a sensitive rendering of her experience with an artisan who has placed over 40,000 "stumble stones" in front of houses throughout Europe where Jews and others victims of the Holocaust had lived before being taken away and slaughtered in the concentration camps. These stones of remembrance are designed for people concretely to stumble over and, in losing their balance slightly, be reminded of the victims of the Holocaust who "fell" to the Nazis. Her article includes wonderful images of stones, paintings, and photographs as well as the story of the "stumble stone" that was placed at the last home of Jewish artist, Felix Nussbaum. It also includes Dr. Breuer's reflections on how the "cultural complex" of her own experience with the Nazi regime and its victims has come alive in her psyche and in her analytic practice. Ruth Breuer was born in Germany in 1940, displaced several times during the war years, and later went to university in Munich as a young woman. She became intensely committed to bridge building in Europe and took a job in Brussels as an interpreter/translator in the early efforts to build a European Economic Community. She later became a Jungian analyst in Brussels, Belgium where she lives and practices. This article was submitted as part of the invitation to all our readers to submit material related to images and cultural complexes.

The second, remarkable contribution to our "stone edition" of ARAS Connections is from Joel Weishaus who, at various stages in his life, has been Literary Editor of U.C. Berkeley's student newspaper in the 1960's, a sculptor, art critic, curator, and writer. What brings him to ARAS Connections is his amazing work on stones. In "Splitting the Stone: Toward a Lithopoetics" he quotes alchemist Gerhard Dorn: "Transform yourselves from dead stones into living philosophical stones." This might be said of the grieving woman I met in the Plaka, although I doubt if she would describe herself as "philosophical"--but she certainly transformed herself from a dead stone into a living person. In this ARAS Connections, we are featuring Joel Weishaus' "The Lost Way of Stones". It is a highly original creation in which Weishaus uses the literary tool of "invagination" to combine his insights with those of others in an elaborate poetic reflection on the nature of rock painting. Each reference to the work of others is carefully documented in his notes, but seamlessly integrated into his poetics and images of rock paintings.

We hope you enjoy this edition of ARAS Connections as much as we did in putting it together.

Tom Singer, M.D.

Co-Chair of ARAS Online for National ARAS

Stumble Stones: Mourning and Memory - The Cultural Complex, A Testimony

Mourning is an essential process of the psyche, fundamental to the development of the individual, through the ages, as well as within families and cultures.”

“It has validity at both the individual and the collective level, in the intrapsychic and the interactive.”

“It involves pain, work and discovery”.

(P. C. Racamier, Le génie des origines, Payot, 1992)

Introduction

My aim is to present the concept of a cultural complex. We will see that while this is a new concept within the theoretical corpus of analytical psychology according to Jung, it is one that anthropologists and ethnologists are familiar with. I hope to demonstrate the usefulness of the concept in the clinical work of Jungian analysis.

Above all, however, I wish to share a personal experience which will show how both the individual and the group identity of each one of us is formed by cultural complexes which cause pain, entail work and can eventually lead to a discovery.

A Personal Experience

On July 20th, 2011, I am with a group of 30 or so friends standing outside 22, rue Archimède in Brussels. Gunter Demnig arrives in his small van with his tools. An assistant accompanies him. I introduce myself. With no unnecessary preliminaries, he shows me the stumble stones, the Stolpersteine, which he has created in his workshop in Cologne. I feel the weight of them in my hands and read the text engraved on the plaque. Emotion overcomes me. We kneel down in front of the house and choose the best place to locate them. I prefer to put the stones side by side, rather than one above the other. The electric saw cuts noisily through the bit of paving stone, which must first be cut from the footpath. A cloud of dust blinds those gathered around. Demnig, down on one knee, clears out the space, inserts the stumbling stones, adjusts them, cements them into position, adds sand and water, steps back to check on his work, brushes off the stones, cleans them with a cloth. This quick, precise, professional work accomplished in silence, imposes intense respect and reverence on the assembled group. A sob is heard …

Demnig tells me: “You can’t leave Felix Nussbaum out.”

Hearing these words, I know that the work which I commissioned from him has meaning for him as well, and that our gesture, which belongs to all who have taken part, is right and just.

This is the culmination of a story which began on my birthday in 2011, although it had been building inside me ever since chance dictated that I should be born into my particular family and cultural group.

As a birthday present, Parisian friends gave me the catalogue of the Felix Nussbaum exhibition at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du judaïsme de Paris (2010/2011) which had excited great interest in France and Belgium.

Although I knew his work, I did not know the life story of the artist. I discovered that Felix Nussbaum, a German Jewish painter born in 1904, went into exile in Belgium with his Polish-Jewish companion Felka Platek, herself a painter; that they got married in Brussels in 1937 and were deported to Auschwitz via the Dossin military barracks at Mechelen (Flanders); that they were in the last convoy to leave Belgium and were murdered at Auschwitz in early August 1944. Felix Nussbaum had recently turned forty. A few weeks later, Belgium was liberated. I was taken aback to discover also that for many years I had passed almost daily in front of the last house they had lived in. They lived there in hiding until they were denounced. The house at 22 rue Archimède, in Bruxelles-Ville, lies half-way between my own home and Schuman Square, where the headquarters of our new Europe, a key player on the international stage and keeper of the peace between 27 European democratic countries, is now located.

Read Stumble Stones: Mourning and Memory – The Cultural Complex, A Testimony in its entirety.

The Lost Way of Stones

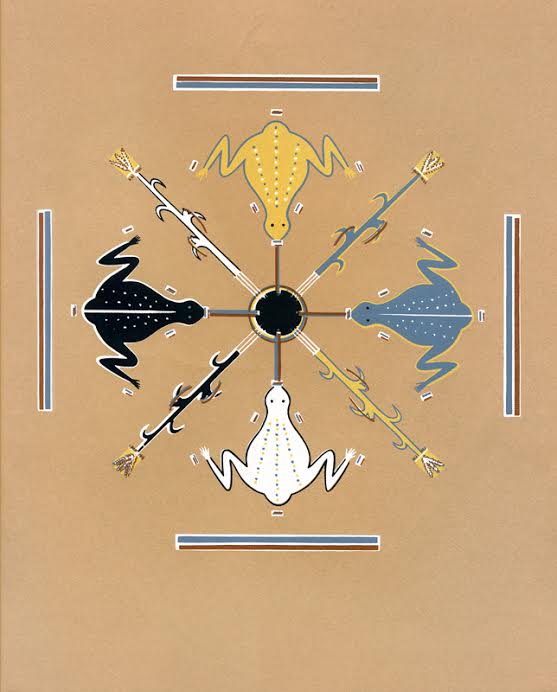

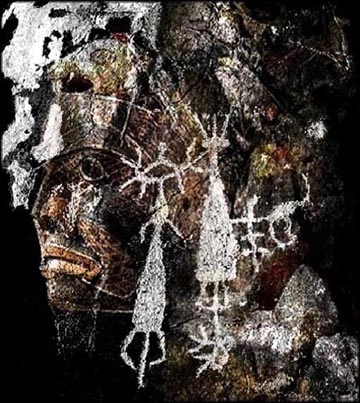

The Lost Way of Stones is built around indigenous rock art found in Southern California, including that of the Chumash Indians who lived mainly along the Santa Barbara Channel and art made by Shoshonean peoples that is located on the Naval Air Weapons Station, near Death Valley, CA. Contrasting human creativity with its destructive shadow, it is "one of the most spectacular concentrations of rock art sites in North America."(2)

Polychrome and monochrome pictographs were painted onto sandstone and pectroglyphs were tapped into dark basalt, art and nature exchanging minerals and patinas of meaning. Archaeologists argue over interpretation, but like the Philosopher's Stone, which does not "allow itself to be held in meaning,"(3) there is no single resolution, only turning and re-turning.

Braque called monumentality space:

My study of Amerindian rock art began during my tenure at the University of New Mexico's Center for Southwest Research. Cataloging slides of rock art of the Southwest also whet my interest in Aurignacian cave art. While the work discovered in the caves reveals a high level of aesthetic sophistication that must have been developing over millennia, most rock art, examples of which are found in over 160 countries, is usually technically cruder are more symbolically varied and culturally evocative. Here Homo sapiens entered the picture, living and creating, naturally and supernaturally, their cultures and themselves. "Thus, all the fine points of human psychology end by expressing themselves in insentient rock. Human legend thus finds its illustrations in inanimate nature, as if stone were inscribed through a natural process. This would make poets our first paleographers—and matter itself profoundly legendary."(4)

During the thousands of years before being rediscovered, cave art was protected because the caves, arduous to negotiate, weren't lived in, but probably accessed only for special occasions, such as initiations into the numinous world. What was perhaps the most sacred art was made in the deepest interior. Eventually abandoned and forgotten, their entrances were hidden behind foliage and debris.

On the other hand, the hoped-for purpose, the sacred task, of painting was to tune in to the invisible—rather in the same manner an anatomical diagram tunes in to the invisible functioning of a living body. And why did the cave artist want to do this? Because rock art is continuously exposed to weathering, and protected from vandalism only by the difficulty of reaching it. Archaeologist Paul Bahn writes that "it was the process of journeying to a location and leaving an image there which counted, rather than the image itself, its appearance, degree of completeness, or durability."(5) However, I would argue that the journey taken and the efficiency of the images made are entangled.

So this is where I arrived, knowing that this place is not a unique place, but that all places are inclusive of countless other places.

In addition to the scientific practice of archaeology, Christine Finn suggests that "a poetic interpretation of archaeology—and by that I mean one that moves into the metaphysical to consider the essence of a 'thing'—should be included in the armory of interpretative tools available to the archaeologist."(6)

As for how digital literary art might relate to archaeological discourse, British archaeologist Christopher Tilley comments:

First we can experiment with organisation of the text itself — the manner in which we inscribe words and statements onto a page. Second we can attempt to break the types of power relation set up between the writer and the reader in texts as constituted at present by attempting to write 'producer' as opposed to 'consumer' texts. Third we can self-reflexively examine ourselves, our subjectivity as writers in the texts that we produce.( 7)

In the following text, the page is a panel, the relationship between writer and reader is open to communication, and the artist works in a self-reflective environment of meditation, research and redaction.

Beginning with a vision of 80 panels, I soon realized that both texts and images request what media critic N. Katherine Hayles calls "deep attention," as opposed to "hyper attention (which) excels at negotiating rapidly changing environments in which multiple foci compete for attention; its disadvantage is impatience with focusing for long periods of time on a noninteractive object..."(8)

Each of the eight "patterned body anthropomorphs" below links to five panels, making a total of 40 texts juxtaposed with 40 palimpsests. There are also references and, as seen above, my trope of invagination, "a fragment of text planted within the paragraphic body, interrupting its continuity and disturbing its literal meaning," is also in play.(9)

The Lost Way of Stones seeks to contribute to rock art studies what, because of specialization, most archaeologists cannot. Proceeding from the assumption that all honest endeavors add to our knowledge of who we are, thus, who we may someday be, this work can only begin to explore the vast range of research and scholarship being generated in rock art studies and accordant fields.

Explore the entire project.

Contents

Become a Member of ARAS!

Become a member of ARAS Online and you'll receive free, unlimited use of the entire archive of 17,000 images and 20,000 pages of commentary any time you wish—at home, in your office, or wherever you take your computer.

The entire contents of three magnificent ARAS books: An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, The Body and The Book of Symbols are included in the archive. These books cost $330 when purchased on their own.

You can join ARAS Online instantly and search the archive immediately. If you have questions, please call (212) 697-3480 or email info@aras.org

We Value Your Ideas

As our newsletter grows to cover both the ARAS archive and the broad world of art and psyche, we're eager to have your suggestions and thoughts on how to improve it. Please send your comments to info@aras.org. We look forward to your input and will reply to every message.

Subscribe

If you're not already a subscriber and would like to receive subsequent issues of this newsletter by email at no cost, e-mail us at newsletter@aras.org.