ARAS Connections: Image and Archetype - 2024 Issue 2

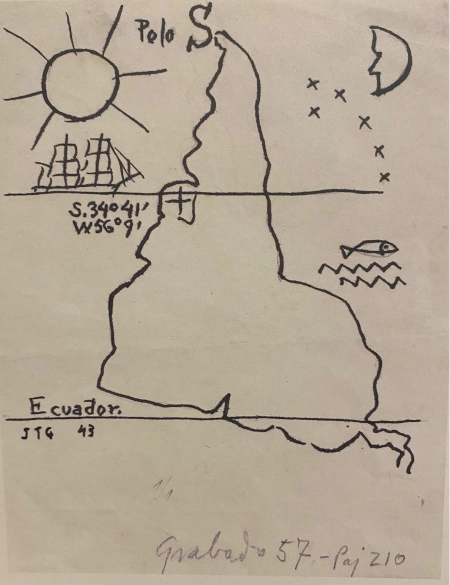

In this edition of ARAS Connections we present three different perspectives on the myth, art and ritual of South America. While attending the first ever IAAP conference in South America, in Buenos Aires, in 2022, I encountered Uruguayan artist Joaquin Torres Garcia’s “Inverted Map.” It served as a startling reminder of the need to emotionally and intellectually recalibrate—as he did visually—the ever-present Euro-centric lexicon. Torres participated in that Eurocentric dialogue and then rejected it. He was a contemporary and collaborator of such artistic luminaries as Gaudi and Kandinsky. But upon returning to his homeland, Torres established a visionary new art school, declaring as his credo, “our North, is the South.” This perspective echoes a famed refrain from a poem written by his countryman, Mario Benedetti: El Sur También Existe, (The South Also Exists)—an oft repeated Latin American call for inclusion, set to music and made popular by musician and activist Joan Manuel Serrat.

The South Also Exists

(English translation by Paul Archer of 'El Sur También Existe' by Mario Benedetti)

With its worship of steel

its giant chimneys

its covert wisemen

its siren song

its neon skies

its christmas sales

its cults of god the father

and military epaulettes

with its keys to the kingdom

the north is the one in command

but here down

below ever-present hunger

rootles through the bitter fruit

of other people's decisions

while time passes

and parades pass

and other things get done

that the north permits

with enduring hope

the south also exists.

with its preachers

its poisonous gases

its Chicago school

its landowners

with their luxury clothes

on a skeleton of poverty

its depleted defense

its defense spent

spent on invasions

the north is the one in command

but here down

below hidden away

are men and women

who know what to hold onto

making the most of the sun

and also eclipses

setting aside the useless

and using what works

with its age-old faith

the south also exists

with its french horn

and its swedish academy

its american sauce

and its english tools

with all its missiles

and its encyclopedias

its star wars

and its lavish malice

with all its accolades

the north is the one in command

but here down below

close to the roots

is where memory

forgets nothing

and there are people living

and dying doing their utmost

and so between them they achieve

what was believed impossible

to make the whole world know

that the south also exists.

The conference galvanized a collective interest at ARAS to explore and develop the number of South American images, symbols, and myths presently underrepresented in the Archive. With this objective in mind, we formed an exploratory team of analysts and candidates from the Andean countries of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru to encourage a more reciprocal south-north/north-south relationship. The initial working group will gather and analyze symbolic material from each country. Analysts or candidates belonging to other developing Jungian societies throughout South America who would like to contribute to this effort are asked to contact Allison Tuzo at ARAS or contact Cecilia Davila or Ana Tibau for Ecuador, Eduardo Carvallo or Monica Pinilla for Colombia, and Patricia Llosa for Peru.

Our initial efforts at “picture hunting,” as ARAS inspiratice Olga Frobe-Kapetyn labeled her own image gathering work, have been through research and visits to museums, universities and other academic and cultural institutions. This brief video from a trip to the Museo Mindalae Otavalo in Ecuador provides an impression of the dialogues that are emerging.

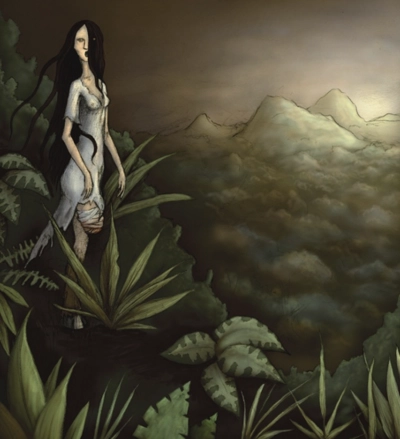

We begin our exploration of Latin American myth and image with Colombian analyst Ines de la Ossa’s study of the myth of the Patasola, a one-legged woman who haunts the jungle. Through her work De la Ossa seeks to disentangle the archetypal roots of the undervaluation of the feminine in Colombian culture. She explores the exile of the feminine within the cultural complex as well as the inherent potential for redemption in its telling.

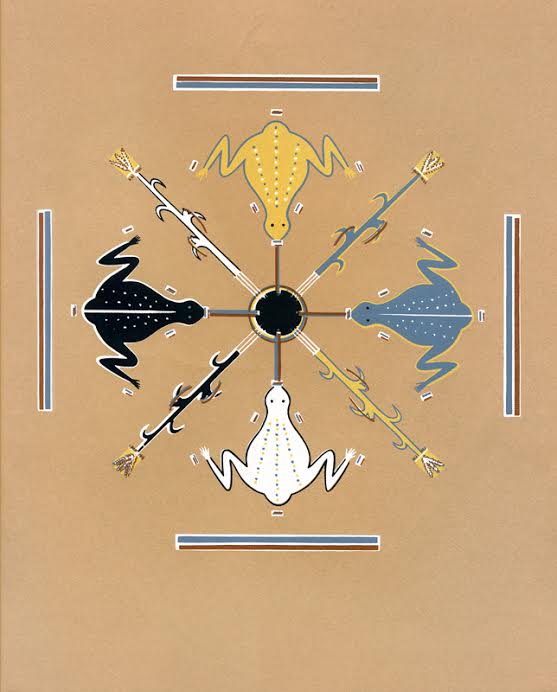

In the second piece we shift to Venezuelan analyst Eduardo Carvallo’s reverie on his initial encounter with pre-Columbian art. He muses about the possible meanings of three works of art chosen from Colombia and Ecuador, which are born out of the depths of oral tradition and an epistemology that is radically different from western understanding. His amplifications are a circumambulation of the art in an attempt to come into contact with its shrouded mystery and meaning.

The third offering is a short documentary video and travelogue essay that introduces the concept of Ayni, a central tenet of the Andean worldview of reciprocity and mutuality at every level of life, explored in relationship to an annual festival of the Aymara people of the Bolivian and Peruvian altiplano and filmed in the city of La Paz.

This edition of ARAS Connections initiates an exploration of a vast South American mythological territory and celebrates ARAS’s commitment to reciprocal cultural dialogue.

The Patasola: archetypal roots of the feminine identity in exile in a Colombian myth

Prayer to the Patasola

‘Patasola, Patasola, I am sorry you live alone, but if you dare to attack me, I will cut off your crutches. You’d better go and pack your bags’. (Creepypastas y paranormales/Facebook)

According to oral tradition, when walking through the Colombian Amazon, the verses of this prayer must be repeated as a way of protection. The Patasola (one-legged one) is a hidden, disconnected yet threatening presence. Who is the Patasola? What does this mythological presence represent? How does this prayer for protection emerging from the Colombian cultural collective speak to us?

Current situation of violence against women and the feminine in Colombia

Being a woman in a predominantly Western culture that has been overwhelmingly patriarchal for millennia implies a great challenge for the evolution of feminine consciousness. The current upsurge in violence against women in Colombia is alarming.

According to Corporación Sisma Mujer, in Colombia, every 13 minutes, a woman is assaulted by her partner or ex-partner; every half hour, a woman is a victim of sexual violence; and every four days, a woman is murdered by her partner or ex-partner. In 2016, various types of gender-based violence increased, such as intra-family, sexual and interpersonal violence and femicide. Femicide is the murder of a woman because she is a woman and ‘is usually accompanied by a series of actions of extreme violence and dehumanizing acts, such as torture, mutilation, burns, cruelty, and sexual violence, against women and girls who are victims of it’ (https://es.wikipedia. org/wiki/Feminicidio). This is due to the normalization of gender-based violence against women, who are dissuaded from reporting the violence they suffer, constituting a social fabric of individual, collective and institutional silences, even transferring the responsibility from the perpetrator to the victim and thus revealing patterns of violence, invisibility, denial, and silence (Corporación Sisma Mujer 2017).

The upsurge of this type of violence is linked to the work of female leaders and human rights defenders who have come out into public life to denounce femicide, and to work for the protection of the rights of girls and women. This type of protective action represents a risk factor for women (ibid.).

Making the Invisible Visible: A Brief Exploration of the Human Psyche through Pre-Columbian Art

The first time I encountered a wide range of pre-Columbian art was during a trip to Machu Picchu, Peru. What I saw at that moment was mind-blowing.

I. Cuzco: A City Built on Top of Another City

When you land in Cuzco, your first impression is that of a charming Spanish colonial city. You quickly find the main square and the Cathedral, recognizing the typical structure of cities built by the Spanish conquerors. However, very soon, the presence of indigenous culture begins to capture your attention.

The contrast between the European traits and the distinctive Peruvian traits is striking. Gradually, you notice differences not only in appearance but also in attitude and demeanor. Alongside the confident manner of most foreigners, you see the cautious and shy behavior of the locals. Their expressions to my mind reveal a kind of sadness or loneliness.

As you walk through the city, you discover Cuzco's history: the main buildings, symbols of the Spanish Crown's power, were constructed over the ruins of ancient Inca structures. The ruins reveal a traumatic history of violence and destruction brought by the Spanish conquerors. This history explains the sad expressions on the faces of the descendants of the conquered Incas. It is the same expression we recognize in our patients and others who have been traumatized. Despite the years that have passed, they still bear the stigma of the clash between the Europeans and their ancestors.

From a psychological perspective, our perception of reality is deeply influenced by our personal history. The Ego complex can eclipse our awareness of the Self, and our Objective Psyche can be obscured by our prejudices and rational frameworks built through previous experiences. Similarly, our patriarchal and European education has limited our ability to experience other dimensions of reality.

Ayni

Today For You, Tomorrow For Me.” This is the meaning behind ayni, a living Andean philosophy and practice that awakens a balanced and harmonious relationship between nature and man. In Andean cosmology, this is expressed through complementary opposites such as male/female; sun/moon; gold/silver. Their interaction is a form of reciprocity called ayni.

One of the guiding principles of the way of life of the Quechua and Aymara people, this equilibrium of exchange and mutuality, which has been practiced since ancient times (since before the Incas), creates a cycle of connectivity and support essential to social and spiritual wellbeing. Anthropologist Catherine Allen describes it beautifully: “At the most abstract level, ayni is the basic give-and-take that governs the universal circulation of vitality. It can be positive … or … negative …. This circulation … is driven by a system of continuous reciprocal interchanges, a kind of dialectical pumping mechanism. Every category of being, at every level, participates.”

I grew up in Peru in the 1970s. Lima, its chaotic metropolis, was still alive with a deep imbalance—a colonial attunement to Europe and America that offered a blind eye and deaf ear towards the riches of the native culture. At that time anything that carried a whiff of the local indigenous was usually subject to derision. A white person wearing a sweater with a llama on it could be only a tourist. While this split between indigenous and modern Western attitudes has changed greatly over the last thirty years, I personally knew nothing of ayni until I left the country and traveled the world.

But I returned to the land of my birth and childhood with new eyes and ears.

Read Ayni in its entirety here.

Little Wishes: The Alasitas Festival of La Paz

Throughout the year craftsmen and ordinary citizens of all levels of skill prepare miniatures to be sold in the streets of La Paz, Bolivia during the annual Alasitas festival in January. The miniatures are of food, cars, homes, building tools, computers, diplomas, condoms; they run the gamut of human needs and desires and are purchased for a nominal fee by those who wish to acquire the reality that the miniature represents.

A tradition of the indigenous Aymara community of the Andes, the central idea of the event is Reciprocity and Exchange. You cannot, for example, make a miniature of your own, rather you acquire one through exchange, i.e., in this day and age, the exchange of money. After a miniature is bought, it must be blessed—by a shaman (yatiri), a Catholic priest, or both as this is a pre-Columbian ritual that has been absorbed into the local Catholic lexicon. Noon is the most potent hour for dreams to be blessed and fulfilled, although blessings do go on throughout the day.

The miniatures are often “carried” or protected under the auspices of the Ekeko, a pre-Columbian god of good fortune and abundance. The Ekeko’s generative powers activate the miniatures in his care—in exchange for favors bestowed upon him by a person who keeps his image.

Peruvian-American filmmaker and artist Patricia Soledad Llosa captures the flow and feeling of this unique ritual day in her short film LITTLE WISHES. She takes the viewer along as, like most inhabitants of La Paz on that day, she shops for miniature representations of her dreams. In a quick succession of sensitive encounters, we meet fellow shoppers and dreamers, sellers, and an elderly shaman—and experience first-hand the wonder of this vibrant and compelling cultural tradition.

Contents

Become a Member of ARAS!

Become a member of ARAS Online and you'll receive free, unlimited use of the entire archive of 17,000 images and 20,000 pages of commentary any time you wish—at home, in your office, or wherever you take your computer.

The entire contents of three magnificent ARAS books: An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, The Body and The Book of Symbols are included in the archive. These books cost $330 when purchased on their own.

You can join ARAS Online instantly and search the archive immediately. If you have questions, please call (212) 697-3480 or email info@aras.org

We Value Your Ideas

As our newsletter grows to cover both the ARAS archive and the broad world of art and psyche, we're eager to have your suggestions and thoughts on how to improve it. Please send your comments to info@aras.org. We look forward to your input and will reply to every message.

Subscribe

If you're not already a subscriber and would like to receive subsequent issues of this newsletter by email at no cost, e-mail us at newsletter@aras.org.