ARAS Connections: Image and Archetype - 2017 Issue 2

ARAS Connections welcomes Ann W. Norton and Andreas Jung as the newest contributors of superb articles from the ongoing Art and Psyche Conferences, the most recent one taking place in Sicily, 2015. The editorial group of Linda Carter, Diane Fremont and Ami Ronnberg has created in Art and Psyche a rich forum for exploring the relationship between image, symbol and psyche. ARAS Connections is fortunate to publish articles from the Art and Psyche conferences as ARAS is constantly striving to find better ways to bridge the inner and outer worlds, to bridge the individual and the community, to bridge different cultures and their unique symbolic material. At the heart of this endeavor is the image.

At our May meetings of the National ARAS Board we pledged ourselves to search for effective ways to bring a symbolic attitude into the world through education and curriculum development. Simultaneously and with great excitement, we also pledged ourselves to expand underdeveloped areas of the archive and have initiated collaborative projects in India, Taiwan, Japan, and China. The ARAS way of developing new projects is to start small, while thinking big for the long term. For instance, it took eleven years to slowly bring to fruition The Book of Symbols which has now been translated into 6 different languages and remains a Taschen worldwide best seller. A current example of starting small with an emerging grander vision is the Pioneer Teens Project—a summer intensive and year long internship for young students to learn about the symbolic attitude. This program has become a small gem in ARAS’ efforts to reach out to the world in a creative way. We are now in the beginning stages of developing a curriculum based on the ARAS Pioneer Teens program experiment which could be used in a variety of settings.

We welcome your ideas for how we can grow ARAS in a way that is true to our unique way of approaching symbolic imagery and bringing it into the world.

Introduction

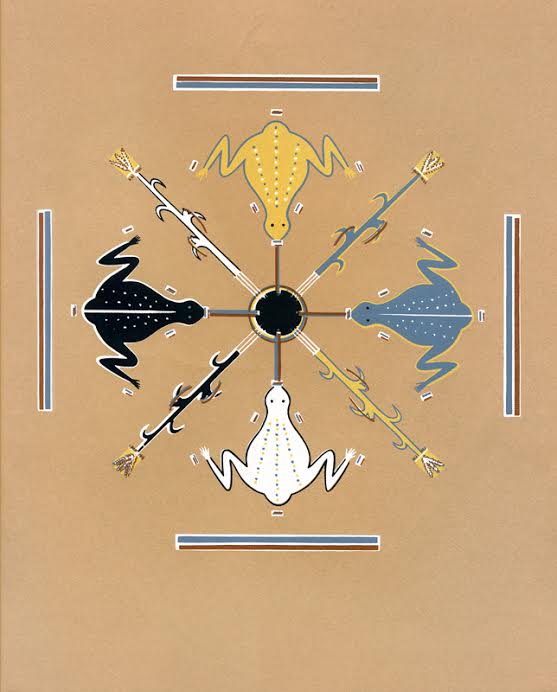

In this issue, readers will find an article by Ann Norton called “Following Bronze Age Migrations” and another by Andreas Jung on the “Shield of Achilles.” Both are well researched, scholarly papers that return us to ancient times; their writing styles are accessible and invite us into ancient worlds and cultures and both offer pictures that open the visual, mythic imagination. We are most fortunate to have two such experienced writers contribute their work to our online journal.

These papers began as presentations for the third Art and Psyche Conference called “Layers and Liminality” that took place in Siracusa, Sicily in September of 2015. We are now in the midst of planning a fourth conference for March 2019 to be held at Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara. More details will follow soon!

Following Bronze-Age Migrations

Jung has emphasized the importance of the collective unconscious in relation to cultural and personal understanding. Study of history, expanded through archaeological finds, continues to shed more light on many elements of the past, making them meaningful in our own lives. Through modern scientific methods such as DNA, carbon 14, metal analysis and geological studies, dating can be more accurate, and a growing number of facts are found.

Added to all of this must be migrations, as humans and their cultural activities are not always static. Therefore, when people today trace their ancestry back to Africa, Ireland or Japan, this does not take into account the many moves and dislocations that went on before. Mass migrations may be triggered by war, famine, or other catastrophe. And when groups of people move, they take with them not only some aspects of their worldly goods but also religious beliefs, language, and customs. This is a study of the cause and effects of one mass migration, which began in the Bronze Age and continues its influences today.

Read Following Bronze-Age Migrations in its entirety here.

Shield of Achilles

Plot of the Iliad

Some two thousand years ago a bard would be standing in the middle of a theatre. He would sing the best epic he knew, the famous Iliad of Homer! He would sing of the Greek army coming over to Troy to conquer the town and rescue Helena, the most beautiful woman in the world. He would sing of the rage of Achilleus, the great hero of the Greeks.

Achilleus is young, handsome and the most brilliant fighter of them all. He is born as son of a goddess, Thetis, and a mortal man. But it is predicted that either he will die in his early years as an outstanding hero or he will live a long life at home as a nobody. Being offended by the Greek commander, however, Achilleus refuses to fight. But he allows Patroklos, his closest friend, to dress in his own armour and join the battle. But there arrives Hektor, the proud leader of the Trojans – he kills Patroklos and takes the armour off.

Now Achilleus' anger turns to sheer rage – further he has no other aim than to murder Hektor for having killed his beloved friend! But how is he to do so? – He has no armour, since it all has been taken. While Achilleus is weeping on the beach in grief and anger, his mother, the goddess Thetis, arrives. And she climbs Mount Olympus to find Hephaistos, the gifted smith of the gods. She asks him to forge new armour for her son. And Hephaistos takes tin, bronze, silver and gold to shape new armour. As a masterpiece he forms a broad shield and decorates it with marvellous pictures.

In his striking new armour Achilleus enters the battlefield and conquers them all. The Trojans escape into town and close all the gates – outside remains only Hektor. Furious Achilleus hurries over and kills Hektor unforgivingly. Then he commits the most dreadful sacrilege – he drags the dead body three times around the grave of Patroklos and leaves it alone - exposed to the flies!

This breach of honour and convention enrages the Gods and they command that the outrage be stopped. Also they send a messenger to Hektor's father, the Trojan king, to lead him through the Greek camp, while all the soldiers are asleep, to the tent of Achilleus. And Hektor's father implores Achilleus, to release his dead son. Achilleus' heart melts and he returns Hektor's body to be buried back in Troy with all due honours.

Shield as Art

And the bard sings of Achilleus' tremendous Shield…

Hephaistos forges the Shield and decorates it with various pictures – you see them coming to life, since the little figures, human beings as well as animals, start to act, to move, to fight. Nine times he creates a different scene, and each has its own content, its own meaning. Hephaistos starts with the world, forms two cities and adds three pictures of agriculture or two of animal farming. Thereafter he creates a wonderful dancing scene and completes his work with an image of the Ocean.

Read Shield of Achilles in its entirety here.

Become a Member of ARAS!

Become a member of ARAS Online and you'll receive free, unlimited use of the entire archive of 17,000 images and 20,000 pages of commentary any time you wish—at home, in your office, or wherever you take your computer.

The entire contents of three magnificent ARAS books: An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, The Body and The Book of Symbols are included in the archive. These books cost $330 when purchased on their own.

You can join ARAS Online instantly and search the archive immediately. If you have questions, please call (212) 697-3480 or email info@aras.org

We Value Your Ideas

As our newsletter grows to cover both the ARAS archive and the broad world of art and psyche, we're eager to have your suggestions and thoughts on how to improve it. Please send your comments to info@aras.org. We look forward to your input and will reply to every message.

Subscribe

If you're not already a subscriber and would like to receive subsequent issues of this newsletter by email at no cost, e-mail us at newsletter@aras.org.