ARAS Connections: Image and Archetype - 2020 Issue 1

Restoring the Sympolic to the Symbolic

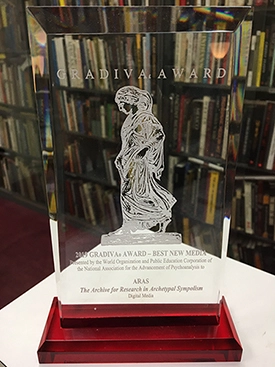

ARAS Connections was recently awarded the Gradiva Award for best e-magazine of 2019, an unexpected and great honor. We are extremely grateful to the National Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis (NAAP) for choosing us for this award. The actual trophy is a stunning 8 inch high glass tablet with the image of Gradiva etched into the glass. Only on closer inspection did we discover that the inscription of the word “Symbolism” as it appears in our name on the trophy was misspelled as “Sympolism”.

The misspelling touched a funny bone in all of us at ARAS that left us playing with the sound and meaning of the misspelling for some time. Without quite knowing why I began to think “what is the difference between symbolism and sympolism? Why did it strike me as funny?” I think it is because, in addition to being a simple misspelling, on another level it is a perfect unconscious concretization of the fact that it is very difficult to bring a truly symbolic attitude into the modern world without it becoming “sympolism”. What does “sympolism” make one think of? Because it sounds like “simpleism” it suggests the tendency to simplify, to strip the symbol of of its polyvalent depth of meaning and emotional resonance and make it one simple thing.

This is the constant dilemma that we face at ARAS and in the world. How can we bring the depth of meaning and emotional resonance of the symbolic realm into a creative relationship with the everyday life of all of us around the world? Our name itself, The Archives for Research in Archetypal Symbolism, or ARAS, does not lend itself to easy understanding or a feeling of accessibility. Maybe by the time the engravers got to “Symbolism” in our name, they had had enough and wanted to “simplify” it. The fact is that symbols matter deeply to us at ARAS and we are constantly struggling against the tendency to reduce “symbolism” to “sympolism” through the branding and trivializing of our mass media marketing and culture. In this context, this edition of ARAS Connections seems particularly timely because our two authors focus on how trends in contemporary society reflect a hunger for a symbolic attitude. Joan Golden-Alexis explores the interface of the symbolic and contemporary society in “Written in the Flesh: The Transformational Magic of the Tattoo.” And Robert Tyminski shows how alive the hunger for the symbolic is in “The Archetypal Power of Images in Videogaming.” If one takes a “sympolic” or simplistic attitude to tattoos and videogaming, one can miss the depth of the symbolic yearning in this contemporary appropriation of archetypal imagery.

Let me give another example of the difficulty of clearly communicating how archetypal symbols that appear in many different cultures and eras are all around us and effect us in our everyday, contemporary lives. ARAS recently featured a lovely entry about ARMOR in its monthly Archetype in Focus email and posted it on Facebook. Shortly after the posting appeared, in an entirely different context, a very contemporary example of ARMOR as symbol appeared in a CNN article and picture that featured a gleaming Donald Trump Jr. proudly displaying his semi-automatic weapon. The article focused on the fact that the manufacturer of Trump Jr.’s weapon embossed symbolic images originating in the Christian Crusades on the gun’s lower receiver. (The gun also featured an image of Hillary Clinton behind bars). In making the connection between the posting on ARMOR and the image of an armored Donald Trump Jr., ARAS added the Trump image to its Facebook posting. It felt like a synchronistic appearance of ARMOR as a symbol in our contemporary culture wars.

The posting of the Trump image did not make it clear enough that the CNN article actually explored the symbolic meaning of the Christian Crusader imagery and referred directly to the power of symbols. More than one Facebook participant in the thread on ARMOR complained about the inappropriateness of the image and how it was not befitting of ARAS to post such an image. After considering whether to respond or not, ARAS decided to engage directly with the Facebook participants who took exception to the posting. We pointed out that the link to the image also included the CNN text about the symbolism of the image. We said that we were trying to show that the symbolism of ARMOR is alive and well in its potent appearance in contemporary life. One of the Facebook posters responded by saying that he thought ARAS had been “lazy” by simply posting the image of Trump without an explanation or rationale for featuring the image. ARAS had not been clear enough in making sure that the text of the article, and not simply the picture, was highlighted. It was the text of the article that spelled out the symbolism that was such an important part of Trump’s ARMOR. But, after all, who looks to CNN to offer symbolic commentary on the news of the day!!! The same Facebook commenter later posted that it had been he who was “lazy” for not reading the article before commenting. We ended up feeling good and gratified by engaging our Facebook critic who responded in the most thoughtful and surprising way. We actually had a conversation, a dialogue, a real exchange that bridged the gap between “sympolism” and symbolism, between personal contact and more impersonal internet communication. We all know the pull in contemporary life and its barrage of information to skim along the surface as we are carried from one topic to the next, from one image to the next, without taking the time to consider meaning and depth. This is how “symbolism” becomes “sympolism” in which we leap from one simple and simplistic misunderstanding and miscommunication to another. It is the symbolic power of the Tweet that reduces the symbolic to the sympolic. Part of ARAS’ mission is to reverse this trend and restore the “sympolic” to the “symbolic”. That is very hard in today’s world on just about any topic, but it is the goal of ARAS to find good ways to make the reality of timeless symbolic content relevant to our world today. The fact is that symbols are all around us and impacting our psyches all the time. It is ARAS’ mission to bring this underlying symbolic reality into clearer relationship with our everyday reality.

Written in the Flesh: The Transformational Magic of the Tattoo

This paper was presented at the 2019 conference Art and Psyche: The Illuminated Imagination.

To tattoo one’s body is merely one of the thousand ways of conjugating the verb ‘to be’ that fundamental concept of our metaphysics—Michael Thévos

What lies deepest of all in man, is the skin—Paul Valery

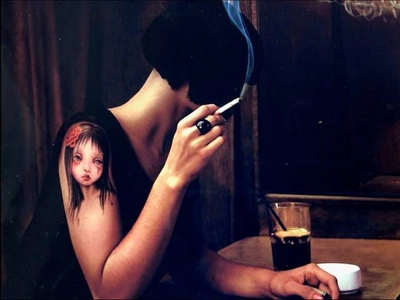

In this paper I am going to approach the subject of the tattoo and the process of tattooing from two perspectives; the socio-political, and the personal. Ultimately, on the most intimate level, in the realm of the personal, I will explore the psychic process of six people who have chosen to tattoo their bodies.

I began my introduction to those who seek tattoos, and particularly the six people in this study, by spending one day each week in various tattoo studios. I listened, and listened, and never spoke. I soon discovered that the relationship between the tattoo artist and the person seeking a tattoo was often exquisitely intimate. The tattoo artist began the conversation by simply asking, “What kind of tattoo do you want?” Within seconds, a breathtaking story would unfold, transforming the moment from the present into something that held something old, and the beginning of something new. The artist would then excuse himself to sketch the tattoo. I marveled time and time, again, at how the artist could fathom so much, with so little information to go on. I never interfered in the dialogue between artist and client; I just listened. After some time, I began to get a feel for those artists and those clients that touched something in me. I began to record what they said, and take pictures. Finally, in order to round out this study, I found what I needed in the stories listed in websites, and from bits and pieces of tattoo videos.

Introduction

In a society that is overtly characterized by untruthful political narratives, moral blindness, marginalization, and violent immigration policies, many of us are living with a growing experience of personal and social exile. The sense of psychological exile aroused by the loss of a social-political context that is responsive to diversity, has increased psychic anguish and emotional numbness on all levels of our society.

Psychoanalysis, in its exploration of the human psyche, was designed to offer the “individual a sense of autonomy, and identity distinct from one’s place in the family, in society, and in the social division of labor.” (Zaretsky, 2004, p. 5). It was intended to develop a growing connection between consciousness and the unconscious, and the development of an ability to reflect, which would allow one to evaluate oneself, and the society in which one lives.

However, In the last several decades, both in academic circles, and as a method of healing, analytic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis, with its central focus on the unconscious and the multilayered psyche, has decreased in popularity. Seemingly, reflective of the current zeitgeist, cognitive therapy with its narrow focus of symptom reduction, and helping one to adapt to the current environment, has taken the lead. As a goal, symptom relief has replaced symbolic understanding of the symptom—that is, the symptom understood as an access point to the unconscious, and to the potentially transformative aspects of the personality. In a society where many of its citizens have a limited access to a psychology supporting such transformations, those living with a profound sense of social exile, and psychic pain (both personal and social), often turn to some form of artistic expression of human truth that can break through this.

Read Written in the Flesh: The Transformational Magic of the Tattoo in its entirety.

The Archetypal Power of Images in Videogaming

Whenever I speak with people about videogames, I usually confess that I know far more about them than I’d ever anticipated. Much of my practice as an adult and child Jungian analyst in San Francisco is with adolescent boys and young adult men, who increasingly are online and typically playing videogames. Many of them are quite alienated and report trouble with forming and maintaining relationships. Often, their videogaming is associated with destructive fantasies that these games reinforce. These videogames frequently make use of apocalyptic settings in which to stage battles and fights for survival.

Alienation once meant insanity, and the word alienist indicated those who worked with the insane. Today, alienation is understood as being isolated from others, lonely and marginalized. As analysts, we appreciate that it also refers to being distanced from the inner world, cut off from the vital life of psyche. It is this barrier to internal processes that interests me in what many males describe when saying, “I’m broken”.

The video games I hear about fall into a category called MOBA, or multi-player online battle arena games. These are point-and-shoot games, in which a player has a weapon and tries to maximize his score by killing as many enemies as he can. These games are mostly played on the Internet. Two examples are League of Legends, released in 2009, and Fortnite, released in 2017. Almost 80 million people play Fortnite each month, and this game generates revenues of over $300 million monthly. Over 70% of the players are male.

An important issue that comes up is whether video games can be addictive. Supporters of these games will argue no and point to unsubstantiated claims that they promote various aspects of cognition and socialization. The New York Times recently reported in depth about the first inpatient rehab facility for video game addiction in the U.S. This article explains that addiction occurs not only to substances, but also to behaviors that become repetitive and difficult to control, much like with gambling addictions and sex addictions. The behavior is primed by an intermittent reinforcement schedule to persist in a false hope of achieving pleasure and satisfaction, both of which decrease with dependence. A neurochemical explanation of this vicious cycle rests in part with the human brain’s dopamine system.

Teams of video gamers now compete for money in what The Economist calls “an adrenalin-filled corollary to social media”, as if there is a demand to intensify what occurs online. Citing the marketing revenues to be made, they write, “Trigger-happy 15-35 year-olds are literally calling the shots.” Many mass shooters are reported to have had compulsive or addictive behaviors around videogaming. In my practice, I often hear fantasies about how a young man or boy hopes to earn a living playing video games. These male fantasies have become more prevalent within the last 5 years. Such aspirations appear to be a new sociocultural trend. A 16-year-old boy recently won $3 million in an international Fortnite competition.

The American Psychological Association issued a report from a task force assessing violent video games. “Consistent with the literature that we reviewed, we found that violent video game exposure was associated with: an increased composite aggression score; increased aggressive behavior; increased aggressive cognitions; increased aggressive affect, increased desensitization, and decreased empathy; and increased physiological arousal.”Their conclusions are based on a meta-analysis of thirty-one articles published since 2009 on this subject. There is much debate about how harmful these violent games might be, and those who support the videogame industry assert that there is no causal link between such games and violence. The authors of this report note that there is no proof of causation to endorse that these games lead to criminal behavior or delinquency.

Read The Archetypal Power of Images in Videogaming in its entirety here.

Contents

Become a Member of ARAS!

Become a member of ARAS Online and you'll receive free, unlimited use of the entire archive of 17,000 images and 20,000 pages of commentary any time you wish—at home, in your office, or wherever you take your computer.

The entire contents of three magnificent ARAS books: An Encyclopedia of Archetypal Symbolism, The Body and The Book of Symbols are included in the archive. These books cost $330 when purchased on their own.

You can join ARAS Online instantly and search the archive immediately. If you have questions, please call (212) 697-3480 or email info@aras.org

We Value Your Ideas

As our newsletter grows to cover both the ARAS archive and the broad world of art and psyche, we're eager to have your suggestions and thoughts on how to improve it. Please send your comments to info@aras.org. We look forward to your input and will reply to every message.

Subscribe

If you're not already a subscriber and would like to receive subsequent issues of this newsletter by email at no cost, e-mail us at newsletter@aras.org.